For hundreds of years, travellers sought refuge in Bukhara as they journeyed along the Silk Road. The city is still a place to rest and, for a while at least, become someone other than your usual self.

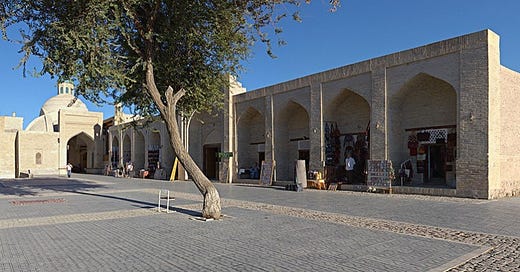

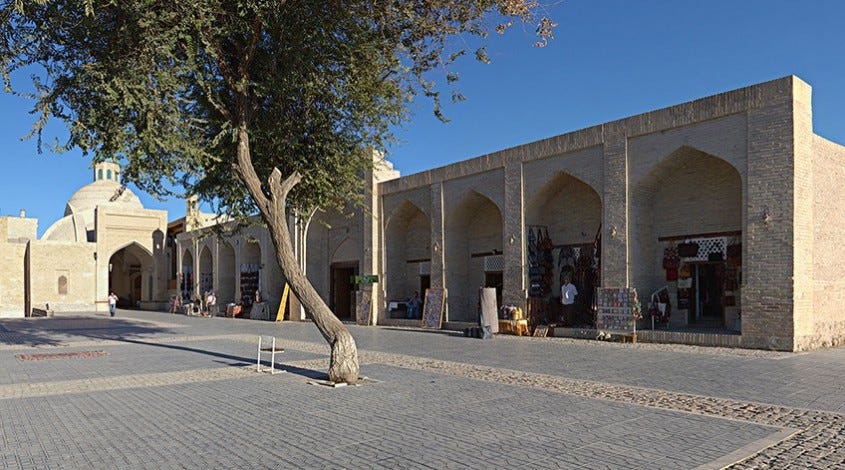

Caravanserais comprised much of this desert city for many centuries but many are no longer standing. Some have crumbled into dust, while others have been restored and converted into guest houses, restaurants, markets or galleries. Their name comes from Persian, with 'carvon' meaning a 'group of travellers' and 'saroy', a house or palace.

They were usually two-storied structures of stone and mud walls surrounding a square or rectangular yard, with thick wooden gates. The ground floor accommodated camels and mules, as well as warehouses for merchandise while the first floor provided space where travellers could spend the night, safe in the knowledge their animals and goods were secure. They traded spice, porcelain, silks, medicines, carpets and jewels.

In medieval times, caravanserais opened their doors to an incredible variety of people, languages, goods and ways of life. Travellers from East and West - speaking many different languages - shared stories, news, merchandise, and ideas while they mingled. They sampled local food and observed foreign manners and customs. They learned about Christianity, Islam, Judaism, and Buddhism from missionaries and scholars passing through. When they continued their journey, they took away many new and different ideas. The economic and cultural exchanges caravanserais made possible had far-reaching effects, still seen today in the languages, faiths and cultures that co-exist in this part of the world. It makes you think, in our world of rigidly held views, how much we would benefit from their return.

We rent bikes and ride out to see the Emir’s summer palace, which is about 10 km from the city. We take what we hope might be a short cut and come across a remarkable monument in praise of Bukhara. Dedicated to the history of the city, it forms the centrepiece of a new park that also houses an amphitheatre and concert hall.

After a rest, we soon find the last Emir of Bukhara’s Summer Palace and wander around its faintly decaying palace and grounds, redolent of a long lost grandeur. It’s called the Sitora-i Mokhi Khosa Saroy, which translates as ‘Palace of a Star like the Moon’. Built with Russian money during its years as a protectorate, it’s an odd fusion of European and Oriental styles. It was completed in 1917 but the Emir lived here for only three years until 1920 when the Russians invaded Central Asia and he fled to exile in Afghanistan. It has a slightly desolate and ambiguous air about it, which somehow echoes the life of its anachronistic emir who reputedly ruled the region with a despotic and corrupt zeal.

On our final day, we visit the Fine Arts Museum, housed in the former HQ of the Russian Central Asian Bank. I’ve been reading about the Bukharan artist Zelim Saidjanov in Colin Thubron’s wonderful books about Central Asia: Shadow of the Silk Road and The Lost Heart of Asia. He writes movingly of his encounters with Zelim, his wife Gelia and mother and I wonder if there might be some of his works in the gallery so ask at the ticket office.

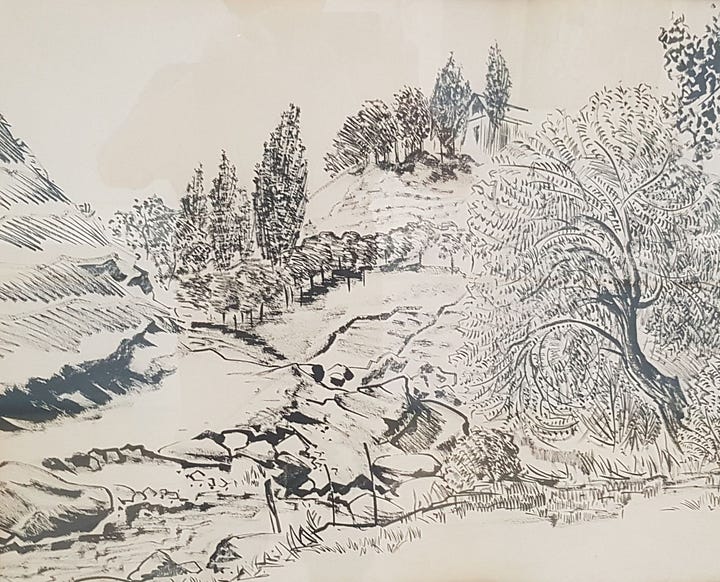

My request creates discussion amongst the staff including a burly security guard who says many things I can’t understand but it’s all good humoured with plenty of smiling so I assume nobody has understood but all is well and we start looking around the gallery. After about ten minutes, an oldish man in his sixties introduces himself. He hardly speaks any English but enough for me to understand that he’s an artist with a studio in the gallery, his name is Muzaffa Abdullaev and he knows Saidjanov. He motions us to follow him to another room, where he shows us a couple of pen and ink sketches by the great man (see below).

Using Google Translate, I ask Muzaffa if any of his own paintings on display. He smiles with modest pleasure and takes us to see his works displayed in another corner of the gallery. His paintings are a complete delight - richly coloured with confidently flowing brushstrokes and brimful of ideas, emotions and playfulness.

My favourite is undoubtedly the brilliantly conceived ‘How Circus Performers Spend Their Holidays’.

It turns out they spend their holidays being circus performers, as demonstrated in this warm, humorous painting. Tightrope walkers show off their skills, jugglers juggle, acrobats stand on their hands, while musicians play long, golden horns (which we will see and hear more of in Khiva). In the shade of a tall, stately cypress, amongst dark rocks and mustard-coloured dunes, a small audience of holiday makers watches the impromptu performances. I like it so much I ask Muzaffa if he and I could have a photo in front of it and one of his other works called ‘Wedding Dance’. He kindly agrees:

By this time, Eil has gone to find a cafe and Muzaffa starts talking animatedly about Zelim Saidjanov although I’m far from certain what he’s saying. We share WhatsApp numbers (I’m pleased to say I still have contact with him today) and I leave the museum in search of Eil and a cup of tea. Just then a bloke approaches me and hands me a mobile phone, indicating that I should listen. On the other end of the line is, amazingly, Gelia Saidjanov who introduces herself in perfect English. I tell her we have been looking for paintings by her husband because I had read about him in Colin Thubron’s books. She replies that she knows Colin well and invites us to their house to see some of Zelim’s paintings. I jump at the chance and we arrange to meet at the nearby crossroads in ten minutes. I find Eil in a local teahouse and we head off to the crossroads full of excitement and anticipation.

Gelia is a small, dark haired, green eyed woman, wearing sunglasses on top of her head, dressed almost entirely in black apart from a turquoise silk scarf draped across her shoulders. She greets us warmly and reservedly and we follow her along dark cool alleys towards their home. Her English is tinged with what sounds like a Russian accent and is so fluent because she still teaches English in a local college. I think their house must have been designed by Escher because we enter the large double doors, descend to a basement and then arrive on a rooftop courtyard. We chat for a while, admire her study through an open window, and then she calls for Zelim.

He appears silently in the courtyard, almost unnoticed at first. He’s tall, thin, grey-haired and stooped as though from years of being bent over a canvas and as we shake hands slowly with him, I recall Thubron’s account:

‘I noticed for the first time his disproportionately powerful hands. ‘Oh yes,’ Gelia said. ‘He used to carry me on his hands like this!’ She held out her palms.’ (p.90 The Lost Heart of Asia). I think of my Uncle Arthur who could split an apple with his bare hands.

Zelim speaks no English and is as silent and ghostly as Thubron’s description of him. He’s wearing a paint-stained pink T-shirt and grey trousers; his feet are bare. At Gelia’s request, he brings out some paintings and props them carefully against the courtyard walls. These works, says Gelia, were painted during lockdown. They’re large abstracts, each one painted in shades of a single colour. Of the four canvases, one is sky blue, one lemon yellow, another rose pink and finally a dark purple. Always the same apparently careless (or carefree) loose brush strokes from bottom left to top right, tapering away as they meet the frame. These final diminishing strokes end at the edge of the canvas and you feel they could have continued had not the dimensions of the frame stopped them. They’re gentle arabesques that seem to match the personality of the tall, stooped man in front of us. They remind me of the hermetic isolation of lockdown, when we were trying to reach beyond the confines of our homes but were unable to do so.

I ask how Covid was for them but Gelia shrugs and chooses not to answer. She says something to Zelim and he brings out one more painting - completely different from the others. A self portrait, says Gelia. It shows a younger version of himself, clad in a wine-coloured cape, appearing to dash headlong across the canvas, as though he barely has time to stay. He sports an old fashioned moustache and a large pointed nose. I say he looks like Freddy Mercury and Gelia thinks Salvador Dali but neither of us mention the silent artist standing beside us in the courtyard. It’s time to leave and Gelia says she’ll walk back to town with us because she needs to buy some fruit. We shake hands with Zelim and when I turn back to wave goodbye, he has already gone.

What an amazing encounter that must have been. I love the circus performers on their busmen’s holiday, very atmospheric and beautifully coloured.

That's a brilliant moment, a brilliant example of, "If you ask, you just never know."