If buildings have secrets then this one must contain more than most. It began life as a maternity hospital in 1931 before becoming, in 1944, the HQ of Albania’s secret police (the Sigurimi) from where it operated a regime of surveillance, terror, torture, imprisonment and execution. Visiting as a foreigner, you can almost feel like an intruder because this is a secret the country needs to tell itself openly, freely and extensively. But they also want to inform and educate foreign visitors who enter its doors not quite knowing what to expect. At first, we can’t quite take it all in but gradually a cold, hard evidence seeps into our bones until we begin to think we know.

You’ll find the Museum of Secret Surveillance in the centre of Tirana, just off Skanderbeg Square. It’s also known as the House of Leaves because of the ivy that adorns its walls and perhaps because of the anaesthetising effect of an association with nature. How do you curate a museum like this? How do you reclaim this building and tell its secret history, having suppressed your first instinct to blow it to smithereens? If you’re as brave as the Albanians then you do something other than destroy it.

You cleanse and scour every inch of this benighted space and only when that’s been done can you start. You collect evidence, testimony, photos, footage and write down what happened here and across the country; you listen to those who suffered and you tell their urgent, terrible stories to anyone who will listen; you gather together the apparatus of surveillance and display it on the walls; you open the doors and say ‘this is what happened to us.’

As I walk from room to room, on a warm October afternoon, I try to take in the volume of equipment I’m seeing. The surveillance devices include: mini cameras, video projectors, recording devices, measuring apparatus, transmitter detectors, headphones, microphones, transmitters, pre-amplifiers, monitors, tape recorders, video/audio control systems, transcription equipment, remote lenses, professional military binoculars etc.

In their sheer number, these objects also tell us about the repression of the individual in Albania during the Hoxha years. Looking at this array of objects, displayed in serried ranks across walls, tables, desks and floors I’m reminded of something else but can’t recall what it is until I get home.

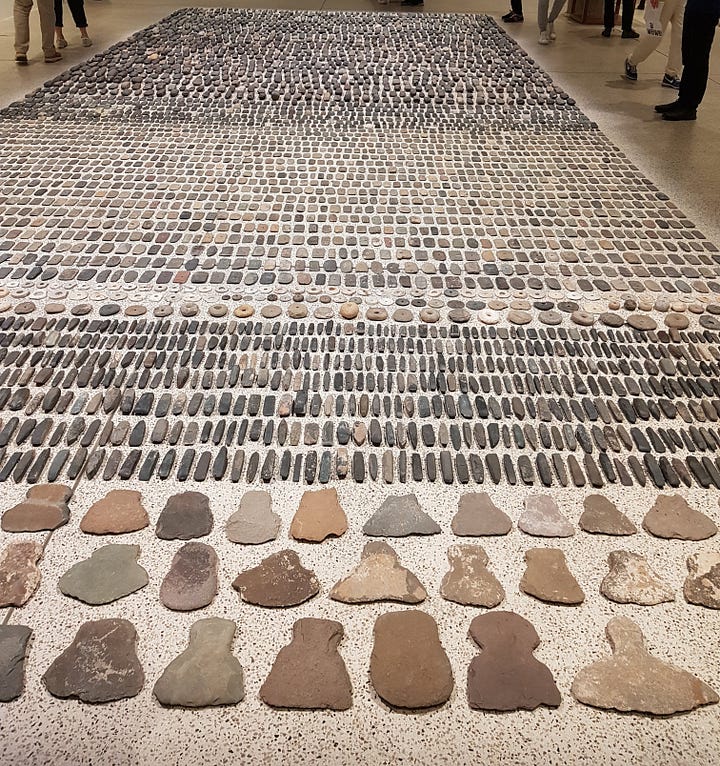

Back in May of this year I saw the Ai Wei Wei exhibition, called Making Sense, at the Design Museum in London. As part of this multifaceted exhibition Ai collected a vast number of artefacts which he displays in similarly ordered precision. Thousands of items, including discarded spouts, broken ceramics, Lego, ancient porcelain cannon balls and Stone Age tools. They are laid out for display in five ‘fields of assembled objects imprinted on the ground of the gallery, appearing like glyphic, patterned readings. The fields are laid out intricately, mathematically even - one between each corresponding row of columns in the gallery - almost akin to a neatly laid out plantation or strictly demarcated public land.’ (from stirworld.com) It’s as though they can be read like lines of text.

Ai calls the field of Stone Age tools ‘Still Life’ with deliberate emphasis on the ambiguity of ‘still’. These tools and what they represent are still life, still vital and still essential to us. The rows of bugging apparatus in the Museum of Secret Surveillance are also still vital and still essential in case we forget what happened in Albania.

One important way of ensuring we won’t forget is by the transformation of these objects into art forms. ‘The arts are at the heart of the matter because they are about our hearts. A society without the arts would have broken its mirror and cut out its heart. It would no longer be what we recognise as human.’ (Margaret Atwood, Burning Questions). In the exhibition notes, Ai Wei Wei says, ‘all I can do is pick up the scattered fragments left after the storm’. He and the Museum in Tirana have done more than just gather ‘fragments’. They’ve preserved, ordered, arranged and displayed them so they speak to us in ways that have the power to change us forever.

There’s an enormous listening device in the garden of the museum. It looks like a loudhailer in reverse and visitors are invited to put their ear to it and discover what they can hear - it’s pointed directly at the city. At first I only hear the traffic that rushes past the building but as I stand, wait and listen it feels as though untold secrets are falling, like leaves, through the autumn air.

A powerful piece of writing Allan. ‘Lest we forget’ comes to mind. We need art to best witness to our common humanity. X x

Nice ending in particular