I’m on the way to Gjirokaster in the south, almost on the border with Greece. It’s the hometown of that most famous of Albanian writers, Ismail Kadare, who died very recently. I’m filled with an undeniable excitement as I leave the now familiar Tirana apartment in search of somewhere shining with new possibilities. I take the number 5 to the bus station and look around for a bus with Gjirokaster on the front. I find one and the bloke beside it says they’re not leaving for an hour so I’ve plenty of time. I’ve previously written about the delightful adventure of Albanian buses here.

An hour later I’m in a battered ancient minibus (called a furgon in Albanian) squashed next to a young lad who smells of burnt toast. We’re full tilt to the south, chasing the heat towards Greece but stopping short in the city of stone. Gridlock on the edge of Tirana slows us down but the insouciant driver tries to make up time later, with bursts of clattering speed along empty rural roads punctuated by the villages, through which we dash seeing only a blur of dusty houses. Billboards blaze in fluorescent colours from unexpected empty valleys, proclaiming the desirability of detergents, flat screen televisions and politicians. Our driver chats to his mate while chain smoking and single-handedly dodging potholes and stray dogs to the pounding thump of Albanian hip hop.

After about five hours (two longer than scheduled because of Tirana gridlock and just, you know, life) we arrive at Gjirokaster bus station. I’d arranged a lift from Vanna, the guest house owner, but she’s long gone and my phone’s not working so I hang around hoping something might happen. A couple of taxi drivers offer lifts but I’m not sure if someone might somehow come back for me. In the end, I nip into a mobile phone shop and ask the lass behind the counter to call Vanna for me. She says she’ll come to get me in five minutes. Top travel tip: the solution to a problem is often to throw yourself on someone’s goodwill.

Vanna and her dad fetch me in his old Merc and we trundle across the cobbles up one of the many hills in town. She’s an English teacher who shares the family home with her extended family, all of whom join in running the guest house, restaurant and shop. For some reason, I have a room for three and a shared bathroom but it all looks good. Five hours in a minibus have left me light headed and uncertain so I take a fitful nap until dinner time.

After dinner I go for a tentative walk, which requires climbing gingerly down a steep cobble stoned slope where I encounter yet more hills and, astonishingly, a large tortoise making its slow, suicidal way across the street. I pick it up and carry it to safety. There’s only me and the tortoise on this strange warm windy hillside.

Stone houses climb the surrounding slopes and find a safe place to cling while dark purple mountains enfold them in silence. The evening empties itself of light as street lamps vapourise, turning cobbled streets into streams of sodium yellow. There is something extraordinary about this place and I climb back up to my temporary home feeling both unnerved and enthralled by where I find myself. It’s a long way from home.

The next morning is humid with weak sunshine filtered through mountain light. I’m not entirely with it after a broken night’s sleep in which I dreamt of loudly destructive tinnitus. But I’m here now and after breakfast I climb down last night’s cobbles and up to what looks like the centre of the city. I’m already breathless in the thin air.

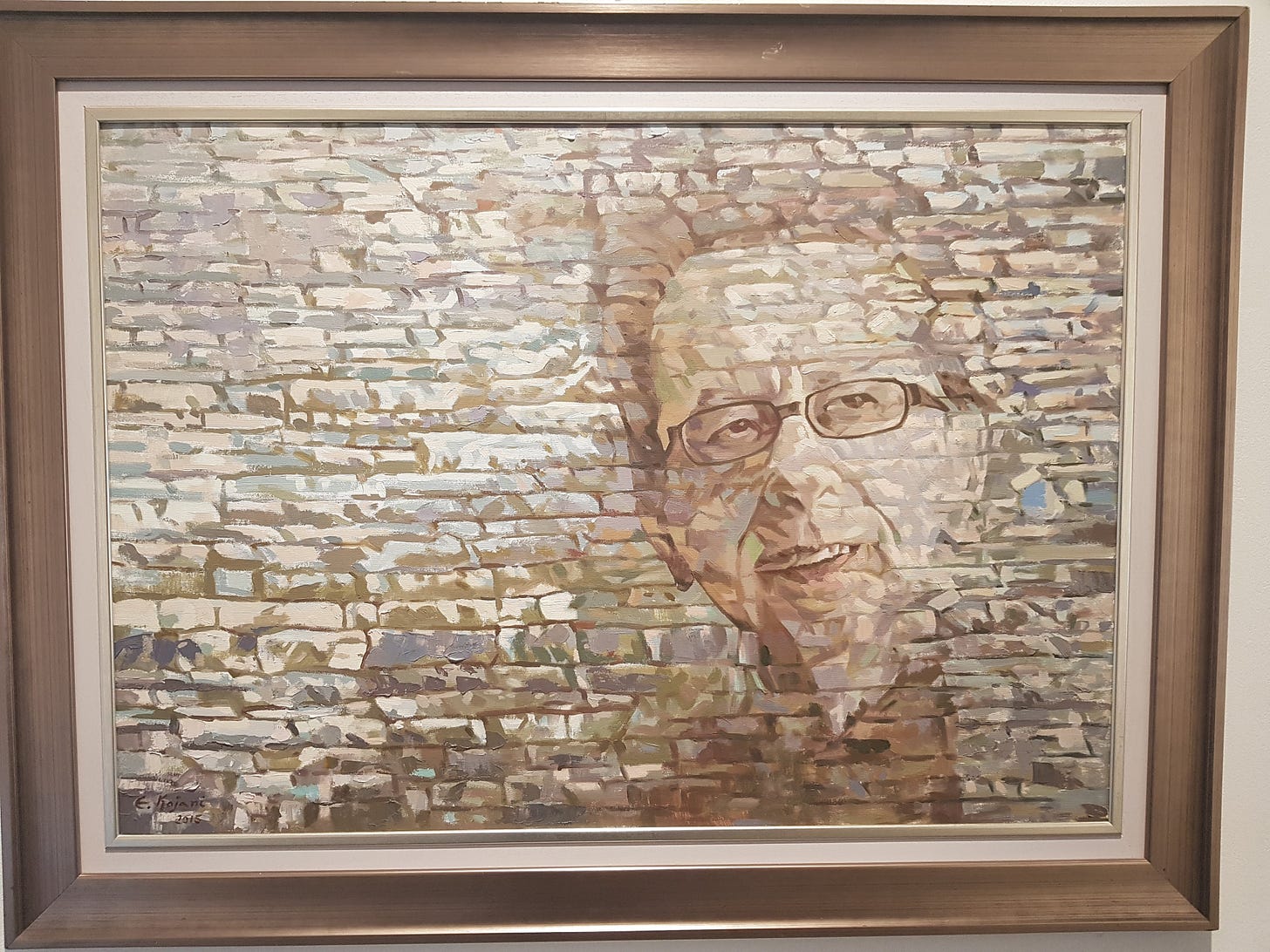

I’m looking for Kadare’s childhood home, which has been turned into a museum. This house and city have been in my thoughts for a long time, ever since reading his Chronicle in Stone and The Fall of the Stone City so I’m excited to be here. But my eagerness is unsettling as I’m unable to follow signposts or understand directions, while the almost vertical streets confuse me to such an extent that I don’t know where I am.

I'm lost in the vertiginous slant of the streets, the white limestone landscape, the huge fortified buildings, the ancient fortress which dominates the neighbourhoods, the breath-taking view across the Drino valley and the surrounding mountains.

‘It was a slanted city, set at a sharper angle than perhaps any other city on earth, and it defied the laws of architecture and city planning. The top of one house might graze the foundation of another, and it was surely the only place in the world where if you slipped and fell in the street, you might well land on the roof of a house.’ (Chronicle in Stone, Ismail Kadare)

This unique topography was important to the character of the writer and the structure of his allusive prose. As he says, ‘the more I learned about the secrets of the art of writing, the more I realised how lucky I had been to grow up in such a unique city, to have got the first explanations about the world by wise old ladies in black, holding a cup of coffee in one hand and a mirror in the other.’ (Preface to Chronicle in Stone). Mirrors enabled these omniscient ladies to see around angled alleyways and know who or what was heading in their direction.

Lacking a mirror, I give up trying to find his house and stop for coffee. I’m not only lost geographically but there’s something deeper, which feels like a lostness of being since arriving in this stone city. It's as though my identity dissolves and I lose touch with who I might be and what on earth I’m doing.

This condition is in the nature of travel and can sometimes be liberating since it enables unencumbered decisions about where to go next, untrammelled by previous choices. Decision making can be clearer and cleaner, with a freeness of movement as identity and ego dissolve in the language and geography of somewhere other.

But it can also induce vulnerability and loneliness, as it does at this moment in this formidable city of stone, which seems to repel and lose me at every turn.

Fortified by caffeine, I decide to try again and ask the lass in the coffee shop if she knows where I can find Kadare’s house. She confidently points me in a direction I’ve already been so I head off without much hope but this time I’m paying close attention and spot a tiny sign almost hidden in the stonework of a corner building.

The moment I find his house, I feel better. The curator is extremely welcoming and friendly and, it turns out, lives near my guest house and asks me to pass on her regards to Vanna. We chat easily and fluently about Kadare, thanks to her excellent English and our shared admiration of him. She invites me to take my time looking around the place and to feel free to ask any questions I might have about the city, the man, his home and work. I step through the open doorway.

Next week: More Stories from Gjirokaster, in which I explore Ismail Kadare’s house and meet the garrulous Norman-san.

I especially like this post among your series on Albania, Allan. Wonderful, atmospheric details.

Excellent atmospheric writing if there is such a thing. Love it. Xxx