Enver Hoxha was born in Gjirokaster in 1908 and ruled Albania from the end of World War II until his death in 1985. After an education in France and a wartime career as a partisan rebel, Hoxha took power and aligned Albania with Stalin in 1944. He remained committed to Stalinism after the Soviet leader’s death, but broke with the Soviet Union in 1962, aligning first with China and then leading the country into isolation from the mid 1970s. His paranoia filled Albania with more than 170,000 bunkers to be used in case of foreign invasion or nuclear attack. State murder, political imprisonment, and internal exile were common practices under Hoxha, with more than 30,000 officers employed in the Sigurimi (secret police).

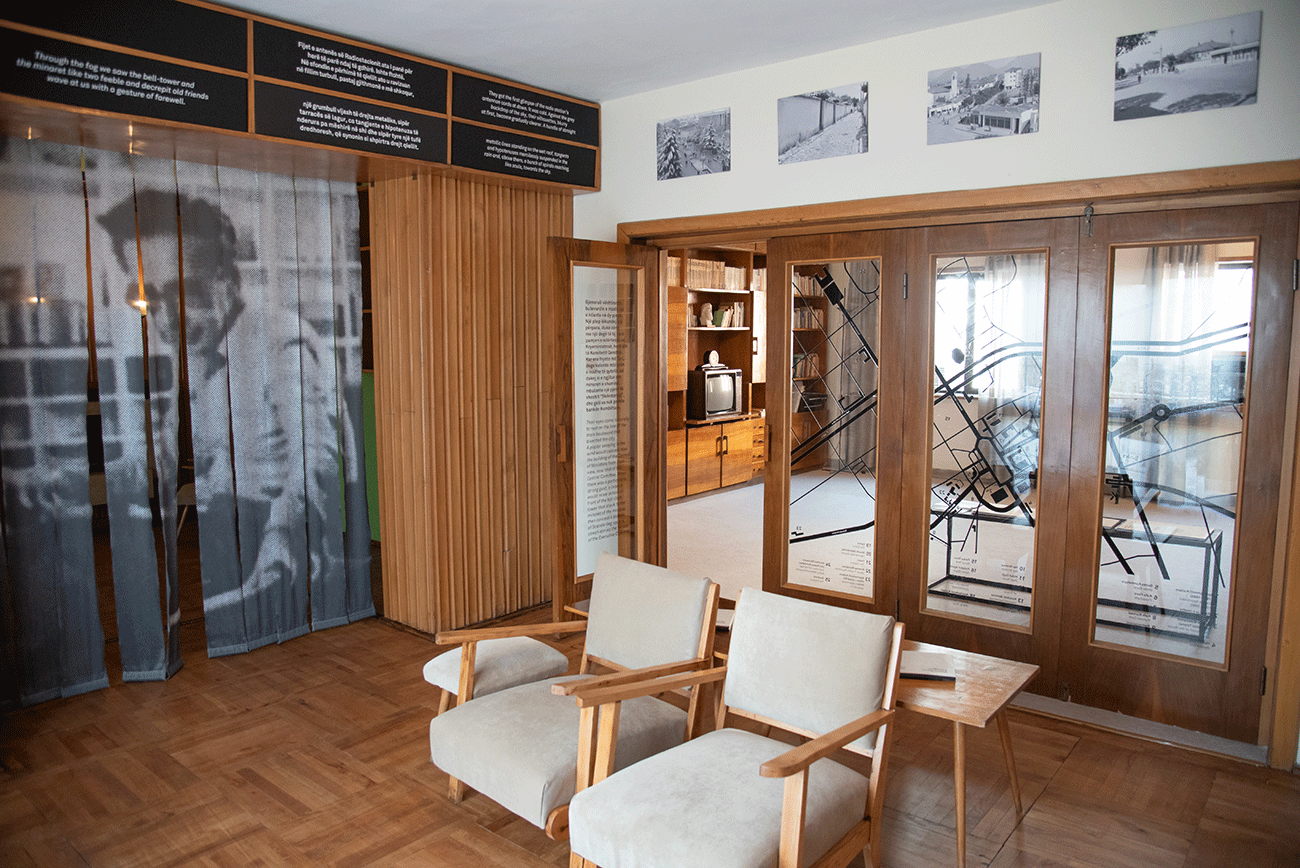

Ismail Kadare was also born in Gjirokaster in 1936, twenty eight years after Hoxha. He was eight when Hoxha came to power. His childhood, as depicted in the wryly intimate Chronicle in Stone, was an immersion course in the ebb and flow of history. He watched three armies march and counter-march through his hometown: first the Italians, then the Greeks, then Hitler's Wehrmacht. Finally, the partisans, led by Hoxha, swept to power in 1944. After school in Gjirokaster, Kadare studied Languages and Literature at the University of Tirana. He won a poetry contest, which allowed him to travel to Moscow to study at the Maxim Gorky Literature Institute. His first novel The General of the Dead Army was published in 1963 and made him internationally famous. He was awarded the first International Man Booker Prize in 2005. He lived, until the 1990s, in an apartment in Tirana (now a museum dedicated to him and his work).

Ismail stands at his apartment window on Dibra Street looking towards the city in the shadows of his reflection. He’s watching Tirana change and grow in a frenzy of nationalist construction: a Palace of Culture; a National Museum; Mosques closed and demolished; a boulevard built for Martyrs. Quarried boulders from Gjirokaster arrive in open lorries, like prisoners on their way to labour camps. The piercing rasp of sharpened saws on stone; limestone dust stings his eyes through the open window; tiles fitting together like gravestones.

He’s treading a meticulous line between what he can write and what he wants to write. Finding a path through history, allegory and myth with meanings as wide and deep as Skanderbeg Square. He’s writing all the time now - he needs to put everything down but then he has to stop and ask himself the same tormented questions. Dare he speak out? Should he write an attack on Hoxha? And if he does, what then? So many have gone before and were never seen again. What are the consequences for him, Helena and the girls? He hears Enver has a soft spot for his fellow Gjirokastrian but is it enough to allow them to survive? Will it one day harden and calcify so he can expect a midnight visit and a knock on the door that will sound like nails hammered in his coffin?

He has this recurring dream in which he’s summoned to the phone by his publisher and it’s Hoxha himself on the other end of the line who heaps unbounded praise on his shoulders and all he can do is sycophantically repeat: ‘Thank you thank you thank you’. He can’t get another word out - throughout the call he’s worrying: What does this really mean? What does Hoxha really think? Why here and why now? Perhaps Comrade Hoxha is simply enjoying a game of cat and mouse?

On better days, they sit at home and transform Dibra Street into ‘Broadway’, quietly and secretly amongst a tiny group they need to trust, because it evokes a wispy, dreamy vision of a photo Helena had once seen of New York. They imagine lights, crowds, neon with a sense of wonder that contrasts with the grey persecutions of daily Tirana. It’s a hidden Broadway of their minds. Yet another secret story he hasn’t written down.

If the Sigurimi come, they’ll strut across the square from the Central Directorate of the Secret Service. They’re no more than a ten-minute march away. In long black overcoats, faceless behind low brimmed hats and dark glasses, arms swinging with military procession. They’ve been listening to Kadare for years but his secrets are too subtle and nuanced to be caught on tape. When they listen back to the bugged recordings, it’s as though the tape is blank - only a silent sibilance. They know he’s saying something he shouldn’t and it’s concealed right there in front of them. His language is encoded with a fictional innocence. Too deep to hear and too opaque to understand. All their surveillance devices can’t catch his words and they can’t catch him.

Like his international reputation, the large square defends him with its very openness. He’s too visible, famous and clever to be caught. His shelves of books protect him like a barbed wire fence. They can’t get at him. His tales of mythic Albania keep him safe - he can hide in half remembered histories and allegorical confusions.

Him and his literati friends, who think they’re a cut above, with all their poems and novels. Bloody writers…making up stories all the time.

An interesting read, difficult at times. I love the lines, ‘language encoded with fictional innocence. Too deep to hear and too opaque to understand.’

And he does look like Elvis Costello!!!

Really coveys the claustrophobia and the stress people must have under being monitored all the time.