The X18: Morpeth to Newcastle

Part 2, in which the Boy from the Green Cabaret changes everything

From Morpeth, the bus heads straight down the A1, picking up speed, until it feels like we’re finally making progress. The top deck sways like an ocean liner while the ex-prisoners bask in lager and freedom, ignoring the rest of us, who read books, look at phones, listen to podcasts or try to see out of the steamed-up windows. After about twenty minutes, we turn off at Melton Park where I grew up. (See Chapel Close)

At this point, the X18 picks up the same route as the 45, which was the bus of my adolescence.

It was the starting point for journeys across the region, including school, except for the days when I bunked off and went straight to Newcastle. During sixth form (which I hated) I probably spent more time wandering the streets of Newcastle than at school, and my A level results reflected that choice. I needed to be on my own: just looking, learning and walking.

It was 1970, I was 17, and there were new worlds out there, beyond the tedium of Pa Stansby droning on about the causes of World War II. There was Handyside Arcade, the Kard Bar, ultima thule bookshop, the brutalist new library, the Golden Egg cafe for chips, and JG Windows where you could hear entire albums, in their listening booths, until somebody noticed and kicked you out. It’s only looking back when I realise what an unadventurous kid I must have been - bunking off school to visit a bookshop and library!

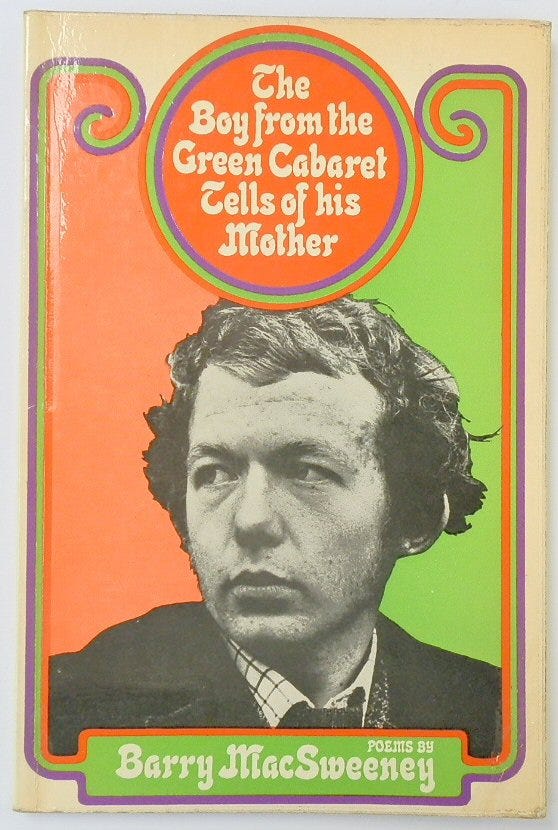

But it was in ultima thule, on one of those bunked-off days, that everything changed around, inside and beyond me. I was in school uniform, feeling acutely self-conscious while an Allen Ginsberg look-alike sat reading behind the desk at the front of the shop. I can’t remember what drew me to the book: was it the intriguing title that mentioned a boy and his mother in a way I’d never encountered before? The jaunty font and colours that made it look like an album cover? The photo of Barry MacSweeney himself - more ordinary bloke than poet? There was something I recognised in that half-worried, mistrustful gaze of his - he knew how I felt. He looked out across the shop, the arcade and the entire city. There was a burning in his eyes that attracted and unnerved me. I was young - there was only my reflection in the arcade window and I couldn't see beyond the school blazer that betrayed me. Even though it scared me a little I needed to know what he knew. I opened the book, read the first poem and that was it.

To Lynn at Work Whose Surname I Don’t Know

The sun always goes down

like this between the

staithes of the High Level Bridge,

dragging a golden plate

across the sewage,

and then breaking it

among the rooftops of the

wharf-side houses and stores,

bending yellow slivers

up the mast of the red tug,

and on the starlings in the

chimney nests,

nooked in the lampblack and grey

shipping offices

above Sandgate.

the dusty navvies

back across the Tyne,

sledgehammer at red-brick walls in the heat,

and slate eves, lugging

concrete heaps and half-bricks

with knotted hankies on their broad heads.

pedestrians this way down to

Mosley Street and back to work.

now i think i will come to you

and ask you and pour the Tyne

and the sun’s bangles in your

lips and hair and bathe your

hands

in

this evening.

I was immediately entranced - this poem wasn't just to Lynn, it was to me. It was, astonishingly, about the High Level Bridge, Sandgate, the Tyne, Mosley Street. It broke punctuation and line-break rules. It was about my life and its locations; the streets I walked and the girls I would never know but still wanted to write poems to. It was as though MacSweeney held out his arms and said (in the same accent as mine), ‘Come here, son, listen. This is how it is. I’m speaking direct to and for you. You’re invited to this world of books, poems, stories and you belong here as much as I do. Come in, you’re welcome. Your awkward naïve shyness doesn’t matter. It’s words that do it. Just write them down.’

The book was bursting with poems about my dull, damp city that transformationally welcomed sunshine and (as I learned later) Rimbaud, Verlaine, Kerouac, Ferlinghetti, Whitman and and and…it was simply wonderful. It was the moment I learned who I was and who I might become. MacSweeney’s sun-filled words blazed through me in an unforgettable epiphany.

Years later, I heard him read at Morden Tower. By then, he’d been through some rough times and life had taken its toll. But he stood proud and strong in his crisp white cowboy shirt and leather string tie. He’d had too close a shave so his face looked sleek and shiny as if it might suddenly burst. He was reading from the Book of Demons with an unremitting urgency that defied the comfortable audience to ignore him. I was moved again by his passionate, prophetic language - those words still got to me.

A blaze of sunshine through the glass roof of the Haymarket bus station catches us unawares, like an unexpected welcome. We’ve made it to Newcastle and we disembark dizzily, like long-lost travellers, remembering to thank the driver for his heroic efforts. We disperse across the city, slightly shell-shocked, wondering if we’ll have the wherewithal to do it all over again when it’s time to go home.

The ex-prisoners high five one another awkwardly. Alpha strides off confidently, looking as if he knows where he's going. Dodgy Accountant slips into Marks and Spencer’s - he’s already heading in the wrong direction for the railway station. Blue Tracksuit puts down his bag and gazes back at the bus as though it might contain an answer to a question he can't quite remember. I think for a moment I could ask him if he's ok but I don't because things like that only happen in stories.

I walk across Percy Street and go into Mark Toney's cafe a few doors up from where Handyside Arcade and ultima thule used to be. There's nobody in here who wants an epic tale of buses, poetry, Rimbaud, and sunshine. They've got their own stories to tell and they’re busy telling them, so I buy a cup of tea and a cheese toastie.

I sit down and start to write.

With age does the memory shine brighter.

How much more colourful is the memory than the reality of the time. Or, are you seeing with the same palette?

Such beautiful writing about such ordinary and extraordinary memories - thank you, as always!