Cities encourage desire. What we want to see or know is always a few steps beyond, always disappearing around the next corner. What if we turn right instead of left? What if we cross the road here and now? What happens if we linger in this square? Who occupied that empty plinth? Who’s that bloke on a horse?

Cities tell us their own enigmatic stories as we walk around them. Walking city streets is an act of creativity; we re-imagine the city and it, in turn, re-imagines us. When Guy Debord came up with the term ‘psychogeography’ in the 1950s it was to describe the effect of locations on our psyches, emotions and behaviours. By the 1990s, British artists like Iain Sinclair and Patrick Keillor were creating books and films based on explorations of places and their meaning through walking.

Debord used the term dérive, which literally means drift, to describe the art of walking in cities. He wrote here: ‘Dérives involve playful-constructive behaviour and awareness of psychogeographical effects so are different from classic notions of journeys or strolls. In a dérive one or more persons during a certain period drop their relations, their work and leisure activities, and all their other usual motives for movement and action, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there.’

It’s a warm Spring morning when I leave my rented apartment just behind Skanderbeg Square so my own dérive begins by reaching this monumental plaza. It's monumental in both senses of the word: it’s about 40,000 square metres and is the largest pedestrianised space in the Balkans. It’s also a monument to spaciousness and stillness in the heart of this increasingly crowded and urgent city. Just around the corner are The Palace of Cubes and The House of Leaves about which I’ve previously written. They remind me of previous walks and other times so that I’m in more than one place at a time.

People inhabit the square at all hours of day and night, becoming their own embodiments of the city. Cyclists, roller-bladers, walkers, discussers, queuers, posers, smokers, schoolkids, old people, tourists, day trippers cross the square and take the air while ancient Skanderbeg rides his huge horse.

Skanderbeg’s statue has an air of permanence about it but this may be deceptive. Although it’s five hundred years since he became an Albanian national hero for resisting the Ottomans, his statue has only been here since 1968. At one time, he rode alongside Enver Hoxha who was given the push by student-led demonstrators in 1991.

Hoxha had previously replaced Stalin in the square when the Albanians and Russians fell out so despite the confident thrust of his impressive beard, it’s possible Skanderbeg’s days might be numbered. As Shelley warns hubristic dictators in Ozymandias:

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare The lone and level sands stretch away.

Skanderbeg Square is the kind of space that encourages drifting and lingering: it’s paved with 130,000 tiles made from 30 different types of native stone gathered from all over Albania. In 2018 it was awarded the European Prize for Urban Public Space. The vast space is actually a low pyramid, with a gentle 3 percent gradient that drains water from the fountains and elevates your eye level in relation to the surrounding buildings.

These buildings resemble a gallery of tableaux arranged to maximise their own magnificence while remaining aloof from their neighbours. The National Museum doesn’t have much time for the Palace of Culture and neither of them show any interest in the grandiose Bank of Albania, while Et'hem Bey Mosque modestly displays itself in the shadow of the five star Plaza Hotel.

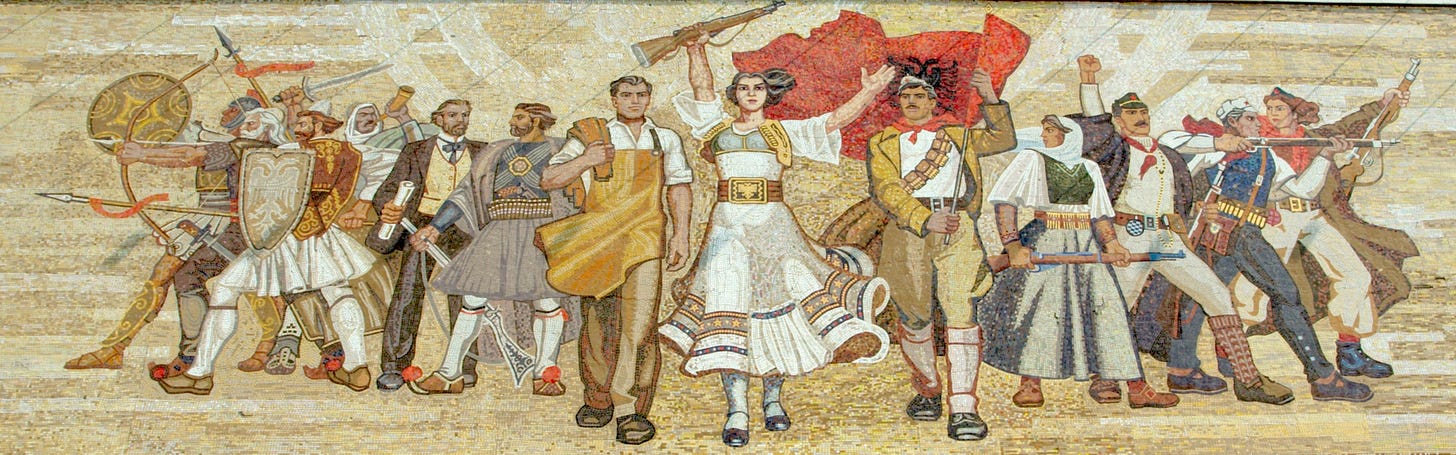

The National History Museum is Albania’s largest at 27,000 square metres and was opened in 1981. Above the entrance is an impressive mural mosaic called The Albanians that depicts figures from Albania's history. This was meticulously restored, tile by tile of Venetian glass, by a team from EU4CultureAlbania.

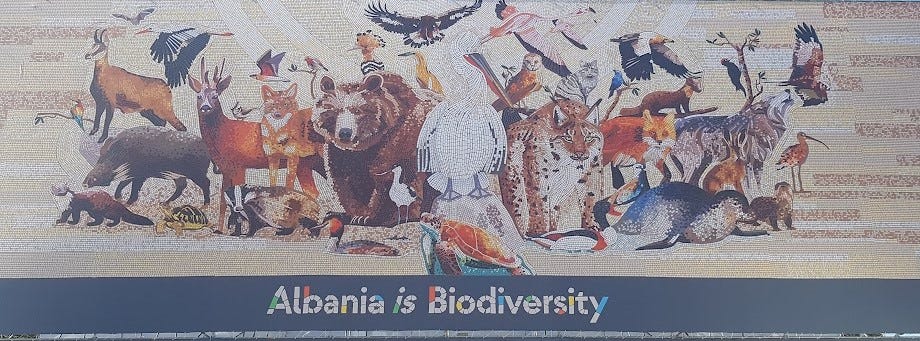

The Albanians love this mosaic so much they enjoy using it in many ways and a recent Biodiversity exhibition in the square produced this clever and playful version:

A short drift across the square is the Palace of Culture, which was built during the Hoxha regime in 1963 with the foundation stone placed by Krushchev. The old city bazaar and historic mosque of Mahmud Muhsin Bey Stërmasi were demolished to make way for this building, in adherence to the regime’s commitment to state atheism.

The architecture is in Soviet brutalist style and contains the National Theatre of Opera and Ballet as well as the National Library. It’s also home to a fantastic bookshop and some popular funky cafes, from which to watch the square as it changes function and form.

Meanwhile the Bank of Albania museum exhibits a collection of all Albanian banknotes as well as helping you understand, by implication, why your lek doesn’t go as far as it used to. The semi-circular building was designed by the Italian architect Vittorio Ballio Morpurgo in 1938 and is also the bank’s headquarters.

The Et'hem Bey Mosque is a small place of worship which was closed but not demolished under communist rule. When it reopened in 1991, 10,000 people attended as an act of defiance, without permission from the authorities. Frescoes outside and inside the portico depict trees, waterfalls and bridges while, five times a day, a muezzin adds his own contribution to the square’s soundscape from the ornate minaret.

Skanderbeg Square is a place where things happen. Many are planned, like the huge screen and playground showing Euros 2024 and celebrating Albania’s progress to the finals for the first time since 2016.

But it’s also one of those urban spaces in which you can, in Debord’s words, ‘let yourself be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters you find there’. Old Skanderbeg is sitting on his horse waiting for you.

Fascinating!